Dictionary of Smoky Mountain and Southern Appalachian English

Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky Mountain English

Michael B. Montgomery and Jennifer N. Heinmiller

ullans2000@gmail.com

jknheinmiller@gmail.com

Abstract

This report describes the Dictionary of Smoky Mountain and Southern Appalachian English, a forthcoming work of lexicography based on historical principles. It discusses the dictionary’s relationship to the earlier Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky Mountainn English and to the Dictionary of American Regional English. Setting out the scope, the primary practices, the purposes, and many other features of the dictionary, this report discusses how the work relies on previously untapped written and spoken sources, including Civil War letters and extensive recorded interviews from an oral history project and how it seeks to capture the speech of one of America’s most reputed cultural areas.

Introduction. The Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky Mountainn English (Montgomery and Heinmiller forthcoming; hereinafter DSASME), now under contract and under final review at the University of South Carolina Press, is an outgrowth of the Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English (Montgomery and Hall 2004; DSME) and is an expansion of the earlier work geographically and chronologically. By incorporating DSME and adding further material from East Tennessee and Western North Carolina, the most concentrated focus of DSASME remains on that part of Southern Appalachia most thoroughly documented and arguably having the greatest salience nationally and internationally.

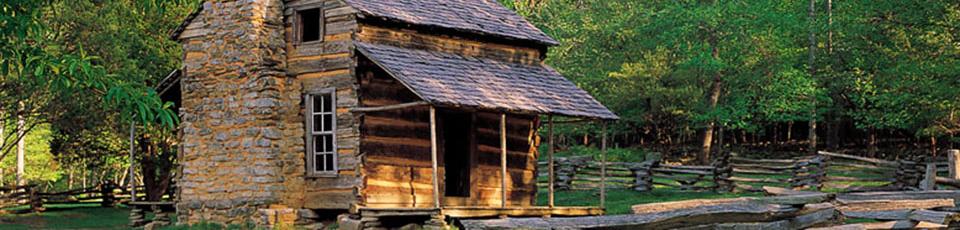

The Smokies. Much had already been written about “the Smokies” by the time Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established in the 1930s (Bridges et al. 2014 contains 1300 references). In part because formation of the park displaced thousands of residents from an 800-square-mile territory, that process resulted in massive, unprecedented documentation of the human and natural life of an area featuring a more diverse ecosystem than any other of its size in the country. That documentation has continued apace to the present day, with the national park attracting researchers from every direction and well nigh every field of investigation.

Beginning in 1937, these researchers included Columbia University graduate student Joseph Sargent Hall (1906–1992), a Californian embarking on what would become a half-century of observing, recording, and compiling the speechways and traditional lore of the few older residents granted life-time leases to remain and many other former residents who had sold their homes and property to settle in communities nearby. Friendships forged and Hall’s curiosity led to periodic onsite collecting of folkloric material as varied as witchlore and dance parties.

In addition to hALL'S 1942 dissertation, several articles, and three popular books of anecdotal material, Hall in his later years prepared a 500-entry typescript glossary, with the intention of depositing it in the Library of Congress for later scholars. In a 1990 visit to Hall, who had retired to Oceanside, California, Montgomery agreed to carry that glossary forward through a comprehensive reading program and to develop a full-fledged dictionary of the mountainous region along the Tennessee-North Carolina border. What resulted fourteen years later and a dozen years after Hall’s death was DSME. Hall’s collections furnished the core of the volume, whose front matter detailed the characteristics (age, level of schooling, level of literacy, types of employment) of every speaker from whom he collected. The dictionary included an extensive sketch of morphology and syntax and other unprecedented features. The Smokies are at the center of a folk culture whose salience, breath of documentation, and wide interest beyond the immediate area justified the relatively small geographical compass of the 2004 volume.

The relation between DSASME and DSME. As the successor work, DSASME retains every significant feature of DSME. The proportion of entries derived from Hall’s collections has decreased from more than twenty percent to less than ten, with the sequel enlarging most entries and adding thousands more to comprise a projected 10,000 (four of which are presented in the Appendix) and 35,000 citations—60 percent more material than DSME[1]. DSASME encompasses parts of eight states, basing its demarcation of Southern Appalachia in large part on that of the Appalachian Regional Commission, from southern West Virginia to northeast Alabama[2]. Every reasonable effort has been undertaken to canvass material from or about this territory to produce the first comprehensive dictionary of an American region based on historical principles, one extending from the late-eighteenth century to the turn of the present one.

Three ways in which DSASME greatly augments and improves historical coverage can be highlighted: rich coverage of the mid-nineteenth century through nearly 2,000 citations from manuscript letters from the ongoing Corpus of American Civil War Letters project; a reading program encompassing hundreds of published sources, including many read by the editor[3] after being identified in the now-completed Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE); and the editing of entries to produce a systematic chronological spread of citations, with the aim of one every fifteen to twenty years in the twentieth century.

To ensure capturing as much research and commentary on the English of the eight-state region as possible, the editor has read in their entirety the hundreds of popular and scholarly publications on the region’s speech listed and annotated at his website (Appalachian English[4]). Especially before the last quarter of the twentieth century, this literature dealt overwhelmingly with unusual elements—the archaic as well as the colorful and innovative—making the speech of Southern Appalachia perhaps the most widely recognized rural English in the United States. Its frequent use by writers of fiction requires that sources be carefully evaluated and citations discriminated for validity and originality. Drawing on experience from throughout the editor’s life and career, DSASME exercises particular caution in citing fiction. That said, it extensively utilizes the works of many authors native to the region, most notably ones from Eastern Kentucky (including Harriet Simpson Arnow, James A. Still, and Jesse Stuart).

The bibliography for DSASME stands at roughly 2,000 items, not counting individual letters, recordings, and other units of larger sources and collections. As with DARE, its entries are sometimes encyclopedic, representing a general reference work that documents speech from a vast range of walks of life, perspectives on the world, social habits and patterns, and more. Traditional culture occupies center stage, for which DSASME produces a collective picture more complete and detailed than does any other source, including the hefty Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Abramson and Haskell 2006). The dictionary’s exhaustive pursuit of subject-area sources, undertaken by visiting libraries and archives in person or through shelf searches online, has tracked down far more items from or about the region than DARE could have done. Many of these are rare, disseminated locally, or, especially in recent years, self-published. The English of Southern Appalachia has long been represented in literature and popular media as both distorted and artificially uniform, giving rise to stereotypes—not infrequently to caricatures— about its form and usage and to misconceptions about its history. It is not surprising that in reality this speech is much more heterogeneous than popularly perceived. Further diversifying the speech documented in DSASME is the fact that Southern Appalachia is larger than generally perceived. It lacks natural or political boundaries, unlike the territory on which other regional works of lexicography have been based. Yet fordictionary purposes, boundaries are required in order to determine whether a given source qualifies for citation.

Here the county-by-county demarcation of the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) has been a steady guide except for some fuzziness on the northeastern and southwestern extremes of the region[5]. For Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States data, the ARC map indicates from which counties in Tennessee and Georgia to draw citations. At the same time, ARC confirmation points to areas needing sources to balance coverage, with North Georgia being perhaps the most conspicuous example. Publications from the well-known Foxfire Project in northeasternmost Georgia promised riches, and the editor was able to track down an extensive set of its early quarterly magazine, only portions of which were used for the better-known series of anthologies published by Doubleday Anchor. Further, works cited by DARE suggested two relevant post-bellum authors from northwestern Georgia: Charles Henry Smith and Will Harben, whose writings were tracked down and read in extenso.

In being a comprehensive historical record of the region’s English, DSASME goes beyond conventional lexicography in numerous ways. Extensive use of manuscripts is just one of these. In addition to the Civil War letters already referred to, the dictionary draws eighteenth- and nineteenth-century evidence from letters, diaries, wills, church minutes, and petitions in manuscript form, as well as from transcriptions published in local historical and genealogical journals. For late-twentieth-century evidence, the dictionary gives primacy to citations directly from recorded oral history interviews of traditional speakers chosen from eleven areas of Southern Appalachia. These interviews, transcribed for the editor’s in-progress Archive of Traditional Appalachian Speech and Culture project, provide more than 3,000 citations for DSASME.

In the field of English lexicography, the proportion of oral material may be unrivaled, with the possible exception of the Dictionary of Newfoundland English (Story et al. 1990). A particular emphasis of DSASME is morphosyntax, meaning that suffixes, phrases, word-order patterns, and other elements of grammar have been fashioned into dictionary entries more so than in any other dictionary of English. Such material is brought together in a section of front matter that represents the most extensive account of morphology and syntax of the region’s speech to date.

The relation between DSASME and DARE. Some discussion is required of the relation between DSASME and DARE, works that have been symbiotic for more than two decades. The editor conferred with his counterparts at DARE through on-site visits in 1994 and 1997 and has maintained frequent contact ever since. Much of his grasp of lexicographic practice and theory comes from Frederic Cassidy, Joan Houston Hall, George Goebel, and their ever-helpful-knowledgeable colleagues at DARE’s home base, the University of Wisconsin at Madison. At innumerable turns, as in entry style and the division of senses, DSASME has relied on DARE for guidance and precedence. As already stated, DARE identified many sources that would otherwise have escaped the editor’s attention. Through the nationwide survey it undertook in the late 1960s, DARE has provided more than 500 citations, and DSASME cross-references nearly 2,000 regional labels that DARE assigns to terms and senses. For example, when DARE posits the range of an item to be “South Midland” (as big ‘pregnant’), DSASME notes this within brackets at the foot of the relevant entry paragraph. DSASME adopts a somewhat simpler format for citations than does DARE. At the head of each one, DSASME usually provides four elements: a date of publication in bold, the last name(s) of author(s) in regular type, an abbreviated title in italics, and a page number (if pertinent), as seen here:

1881 Pierson In the Brush 73

DARE includes up to three other elements for the citation: an identifying location in bold (usually a state, less often a sub-region), a pertinent time frame if it significantly predates publication, and a comma, as seen here:

1962 Dykeman Tall Woman 190 sAppalachians (as of 1877),

When these details can be judged, DSASME usually gives the sub-regional location for a citation and the time period of a source in an annotation at the bibliographical entry, a practice followed to reduce redundancy between entries and to allow for other pertinent information in the bibliography. In its only alphabetic volume published since 2004, DARE V (Sl-Z) borrows more than 150 citations from DSME[6]. Reciprocally, DSASME borrows many citations from DARE when this is deemed useful, as from the vast Gordon Wilson Collection (c1960)[7].

The culture and speechways of Southern Appalachia. The status of the culture and especially the speech of Southern Appalachia is complex and conflicted, even bifurcated. The conflict is encapsulated in the ways natives and others evaluate the speech associated with Appalachia. The region prompts negative images and perceptions—of poverty, poor education, and other social ills. Yet it embodies the acknowledged, widely imitated, often cherished heartland of traditional rural American culture as expressed in music, storytelling, and much more. For many in the region, their speech marks their identity and their attachments. For much of the country and indeed abroad, Southern Appalachia is synonymous with authenticity. Admired for its inventiveness, color, and variety, mountain English attracts the curiosity of a large population beyond those who study it or, as the readership of DSME showed, those accustomed to browsing a dictionary of any kind. Too often scorned and depreciated by mainstream, metropolitan culture and its values, Appalachian English has long needed and deserved the comprehensive treatment that the Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky Mountainn English will provide, the proper understanding that the dictionary will promote, and a higher status for both this speech and its speakers.

References

Abramson, Rudy, and Jean Haskell, eds. 2006. Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Bridges, Anne, Russell Clement, and Ken Wise, eds. 2014. Terra Incognita: An Annotated Bibliography of the Great Smoky Mountains, 1544–1934. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Cassidy, Frederic G., and Joan Houston Hall, eds. 1985–2012. Dictionary of American Regional English. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Montgomery, Michael B., and Joseph S. Hall. 2004. Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Montgomery, Michael B., and Jennifer Heinmiller. Forthcoming. Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky MountainEnglish. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Story, G.M., W.J. Kirwin, and J.D.A. Widdowson, eds., 1990. Dictionary of Newfoundland English, 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. http://www.heritage.nf.ca/dictionary/

Appendix

Sample Citations for the Dictionary of Southern Appalachian and Smoky Mountain English

running go (also run-ago, run and go, run ’n go, runny go, run to go) noun A running start, leap, or attack on, an energetic charge toward or against.

1915 Dingus Word-list VA 189 run-an’-go = a run before leaping. 1939 Hall Coll (Hartford TN) [The bear] wheeled back on the dogs. [The bear hunter] took a run-ago an’ run his arm into that hole he cut into it, an’ run it right up about his heart. 1955 Ritchie Singing Family 21 I snatched up an old broom handle lying in the yard and took a runago at the homemade screen door and rammed that stick plum through. 1956 Hall Coll (Del Rio TN) I took a run-ago at it and just frailed it. Ibid. (Newport TN) She took a runnin’-go at him. 1973 GSMNP-79:17 You could play out in the hallway where they'd waxed it, you know. We'd make that for a slide. Take a run and go and just slide all the way down to the hall and then up again. 1976 Thompson Touching Home 17 take runny go = to get a running start. 1978 Bird Traps 74 Let’s take this umbrella, take a run to go, and jump out that lower door [of the barn]. 1991 Haynes Haywood Home 55 When it was really cold, ice skating on the branches and creeks was fun if we could get away with it. Of course we didn’t have ice skates, so we'd take a running go and slide on our shoe soles. 1998 Dante OHP-51 The train had to go up and go way up here and get a run and go and come back. 2005 Williams Gratitude 519 run ’n go = to back up to get a good start and gain momentum as you run. For instance, if somebody was to try to jump over a fence or high bar, he'd back up and take a run ’n go at it.

[DARE running go n southern Appalachians]

Running go illustrates the challenge of lemmatizing folk vocabulary having no precedent in great historical dictionaries or in Webster’s Third. DARE chooses running go as its headword, based perhaps on parallelism with the synonym running start or on its predominance among citations, though that form, found in three of its eight citations, postdates run-an’-go by four decades. DSASME displays greater variety of forms (6 vs. DARE’s 4), meaning that it cannot fall back on frequency as the decisive criterion. DSASME attests an intriguing variety of ways speakers who have probably never seen the word written have analyzed (or as Jespersen says, “metanalyzed”) the series of three syllables they hear, while at the same time apparently agreeing on its sense.

care verb To be willing or agreeable to, mind (usually in phrase I don’t care to or I would not care, especially as a response to a suggestion or invitation). The verb may range in sense from the understatement “not to object” to the more affirmative “to be pleased if one does.”

1862 (in 1999 Davis CW Letters 83) I dont care if we get to Stay here during the war for I am highly pleased with our Situation. 1862 Patton CW Letters (July 6) I would not care if you could send me a strong pare of janes pants and a pare of sox. 1864 D Walker CW Letters (June 19) I wold not Car if yow wold Send me your liknesses. 1910 Weeks Barbourville Word List 456 (with a negative) = to be willing: “If I had a horse and carriage I wouldn’t care to take you to Boring.” 1921 Weeks Speech of KY Mtneer 16 When my friend in the Cumberlands says, “Now if I jest had a horse and carriage, I wouldn’t care to take you to Camp Ground to-day,” I understand him to say that it would be no care or trouble, but only a pleasure for him to take me anywhere I wanted to go. The family jolt-wagon and mules were at my service, however, and the ride was one to remember. 1929 Chapman Mt Man 510 “I don’t care for work” means “I like to work—I don’t mind working.” And “I’d not care to drive a car” means “I am not afraid to—I’d like to drive a car.” Yet outlanders who have lived years in the mountains are still taking these comments in the modern sense, and advertising that the mountain man is lazy and that he is shy of modern invention. 1931 Hannum Thursday April 52 “Come and set?” “I wouldn’t keer to.” The rising inflection of the guest’s voice indicated her willingness, so together they dropped down in the cool grass. 1937 Hall Coll (Cosby TN) He didn’t care to lay down anywhere [= he didn’t care where he lay down, would lie down anywhere he felt like it]. 1939 Hall Recording Speech 7 Examples of not to care to for not to mind, as in a sentence spoken by an Emerts Cove man, “She don’t care to talk,” meaning “She doesn’t mind talking,” are found in both the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. c1959 Weals Hillbilly Dict 5 When a mountaineer says, “I don’t keer to work,” what he means is that he doesn’t object to working, that he’s used to working, and that he accepts the fact that a man must work to live. 1975 Duncan Mt Sayens Two of my friends, from the Midwest, left a little old lady standing in the road because she replied “I don’t care to” to their offer of a ride. 1978 Montgomery White Pine Coll V-3 They said, “If you fellows are deer hunting up in there, now watch about shooting down on us because we’ll be up there making liquor.” They didn’t care to tell it. 1981 GSMNP-117:27 He said, “I don’t care if you goin’ if your parents don’t care.” 1986 (in 2000 Puckett Seldom Ask 89) If you don’t care to, Sue, would you fix me a sandwich. 1998 Brewer Words of Past Another East Tennesseism is the practice, when asking somebody to do something, of adding “if you don’t care to” when the meaning is exactly opposite of the plain English. An example would be, “Would you carry me to work, if you don’t care to?” 1998 Dante OHP-71 I didn’t care to say what I wanted to to my dad cause I was married and all. 1999 Montgomery File A lot of mountain people are kind of backward, but I don’t care to talk to nobody (40-year-old woman, Del Rio TN). 2005 Bailey Henderson County 32 Now and then he pushed his wilted felt hat to the back of his head and wiped away beads of perspiration that gleamed on his brow. Yet he never slackened his pace and his eyes charted the road ahead as he walked with determined steps. Then someone he knew eased up alongside him.” I’m on my way to town, Will,” the fellow said. “Want to ride wi’ me?” Will looked into the familiar face, and feeling in no way compelled to prove his independence, he answered, “I wouldn’t care to.” Because the driver knew that, in mountain lingo, “I wouldn’t care to” means “I don’t mind if I do,” he waited for Will to open the door and climb in.

[DARE care v B1 chiefly Midland]

The entry for care is important for the idiom I don't care to, which non-natives to the region tend to misinterpret as a negative response, i.e. “I don't want to” rather than “I wouldn't mind at all to.” Just as in DARE, citations instantiate both usage and commentary on usage, in this case the confusion the idiom has generated. Thus, one can translate “a lot of mountain people are kind of backward, but I don’t care to talk to nobody” as “many mountain people are somewhat shy, but I don't mind talking to anyone.”

cat shaking noun phrase See citations.

1932 Dugger War Trails 240-41 Mary Clawson, who was a good match-maker, called from the big house door: “Come in here, boys. We’re goin’ to have a cat shakin’ before dinner.” The quilt had been quilted and taken out of the frames. It had been spread out on the floor with the cotton bats grinning around the edges between the top and the lining. Each boy and girl stooped and gripped the rim of the quilt with both hands and raised it up as they straightened. Mrs. Clawson now threw the cat over into the center of the quilt and all began to shake up and down. The poor cat was perfectly bewildered. For a moment its eyes pleaded with the shakers in vain. Then they bleared with wild excitement, as it rolled from side to side on the quilt. When it tried to leap over on one side, they hurled it back to the other; when it was wriggling to get on its feet, they whirled it over on its back. The wilder the cat’s excitement the harder they shook and the louder they laughed and hallooed; and the greater their glee the wilder the cat became. At last with all its reserved strength reinforced by terrible fright, it made a grand leap for liberty, but just as it reached the border of the quilt it was tossed heels up towards the ceiling, but fell on its feet outside the quilt and went out at the door into the woods with such terrible speed that it looked more like a streak of cat than a cat, and did not come home for three days. 1969 Hannum Look Back 47 They called it cat shakin’—and poor cat! A quilt was laid out on the floor; all courting-age young bent down, took firm hold of its edges with both hands, and raised up with it. Then the cat was thrown in and the boys would try to shake it out toward their best girl. That was the idea of the game; whichever girl the wild-eyed tabby leaped nearest to would marry first. The shakers laughed and yelled as they tossed the oracle of their fate from one to another, and high in the air. [1977 Shackelford et al Our Appalachia 20 There’d be a lot of girls there, seventeen- and eighteen-year-old, helping them quilt. We all would come in of an evening, and we’d want to shake the cat. Four girls—one at each corner—would get a hold of that quilt and another one would throw the cat in, and they got to shaking it as hard as they could shake and whichever one that cat jumped toward was going to get married first ... It happened all over this country at all the workings.] [2011 Houk Quilts 12 Quilts are cloaked in superstition too, like “shake the cat” for example. When a quilt came off the frame, the unmarried women went outdoors, put a wary feline in the center of the quilt, held onto the corners and bounced the nervous animal into the air. Whoever the cat landed closest to would be the next to wed.]

Cat shaking represents an entry that, like more than 2,400 others, relies on citations to do the defining. Encyclopedic as well as lexicographic, such an entry references a regional custom, practice, or the like. To be sure, the tossing of a cat to foretell one’s future mate is now obsolete, as is much of the traditional culture documented in DSASME, but this fact contributes to the uniqueness of the dictionary.

swarp

A variant form sworp [see 1993 in B3].

B verb

1 To strike, thrash, push with a swinging or sweeping motion. See also swap B, swipe, warp 2.

1946 Matthias Speech Pine Mt 192 = to swing, strike, especially with a swinging or whipping motion: “His mother swarped the belt at him through the open door” ... swarp = to wipe or “swipe”: “I like a little [molasses] on my biscuits now and then. Then I like to pour a little on my plate and swarp a hot biscuit through them.” 1982 Maples Memories 29 We would take an old cane pole, swarp [a bat] down, hold him by the wings, and see his little snapping teeth. 1989 Oliver Hazel Creek 31 He cut a large pole and when they would get too close to him he would lash out at them (“swarp” the ground) with the pole to drive them away. 1991 Still Wolfpen Notebooks 59 He grabbed off his belt and he swarped me, and he swarped me with the wrong end of it. 2005 Williams Gratitude 529 = 1) to swat at; 2) to brush harshly against something, as, “The limbs swarped ag'in the ground when the tree fell.” Or tell a youngun: “I'll swarp your hind end.”

[cf SND swap/swop v 1 “to strike, hit”; DARE swarp v chiefly southern Appalachians]

2 To move with a dragging, sweeping, or brushing motion.

1961 Williams Rhythm and Melody 9 Hit won’t be five minutes ’till that bag o’ fleas [=a dog]’ll be right back in hyar a-swarpin’ an’ a-swarvin’ around. 1961 Williams R in Mt Speech 6 = swipe, or possibly swipe + warp. 1976 Bear Hunting 284 The way [bears] wind around and swarp through them roughs and maybe make three or four trips around one knob, why, you may travel a long way. 2003 Carter Mt Home 13 He carried a red ‘kerchief in his back pocket for swipin’ sweat off his face, which flowed freely in the hot summers.

3 To behave or move in an erratic, unsteady, or awkward fashion.

1983 Page and Wigginton Aunt Arie 139 She goes up and down th’road a lot, swarpin’ along. 1993 Ison and Ison Whole Nother Lg 66 sworp = move about unsteadily, from one side to another.

4 To behave riotously or with abandon, “run around,” “raise hell,” especially under the influence of alcohol.

1946 Dudley KY Words 271 = in the pple. form swarping only, the word has some currency in a sense roughly definable as wenching, hell-raising; or more mildly as skylarking, cavorting, playing: “The boys was out swarpin’ (or ‘swarpin’ around’) last night.” The occurrence of the opprobrious sense appears to be spotty; the word is used in the other senses freely and without embarrassment by native speakers who are distinctly modest. 1999 DeRosier Creeker 44 I never heard anyone back home speak of someone drinking; they always said the person was “drinking and sworping.” ... It means wildly running around, cussing and hollering, and in general acting in ways no good, sane, sober person would ever behave. 2007 Preece Leavin' Sandlick 40 He wuz so bad to drank and come in jest a swarpin, trying to fight on Lassie Jo.

[cf SND swap v 1 “a blow, stroke, whack”; DARE swarp v 1 “to strike, hit, smite, deliver a sudden blow upon” (all senses) chiefly southern Appalachians]

C noun A blow, stroke.

1940 Stuart Trees of Heaven 168 You can take six rows at a swarp around a newground slope. It’ll shore look purty to see where you slice down six rows of weeds. 1946 Dudley KY Words 272 Besides a cutting stroke this word as a noun sometimes means a swishing or swinging motion: “One day he gets too sorry to bend and lace his shoes, and it’s a swarp, swarp, every step.” 1963 Edwards Gravel 72 He kept saying “Whoa,” and every time he said it, he gave her another sworp with the withe. 1982 Maples Memories 32 Dad said that he and a friend were riding one day, and the friend, acting smart, reached over and gave Dad’s mule a swarp across the back. [See 2005 in B1.]

[cf SND swap n 1 “a blow, stroke, whack”; DARE swarp n southern Appalachians]

According to DARE, swarp is a term distinctly Appalachian in distribution. It appeared in DSME only in its basic sense of “to strike, thrash.” To some minds familiarity with the fourth verbal sense indicates one's fluency in the regional vernacular. To the practice of citing or cross-referencing an earlier history in England, Scotland, or Ireland, the entry for swarp neatly illustrates three “historical principles”: 1) arrangement of citations by date within a paragraph; 2) arrangement of senses by their presumed development between paragraphs within a given part of speech; and 3) arrangement of parts of speech by their presumed development within an entry. Especially because of the comparatively shallow time-depth of DSASME, few entries illustrate all three principles, notably 2).

[1]In part because of this reduced proportion, the title page will state that DSASME “incorporates the lifetime collections of Joseph Sargent Hall” rather than listing Hall as co-editor. Perhaps more important, Jennifer Nelson Heinmiller joined Michael Montgomery as assistant editor of the dictionary in 2011, and the two have worked closely as Heinmiller has become a lexicographer in her own right.

[2]ARC designates counties as “Appalachian” on the basis of socio-economic profile as well as topography. Accordingly, it qualifies counties in central Alabama, central Tennessee, and central Kentucky, as well as northeastern Mississippi, as “Appalachian” that are many miles from hill country. Many of these peripheral counties are excluded from coverage by DSASME.

[6]Joseph Hall, whose work, as indicated above, formed the foundation of DSME, donated a duplicate of his citation slips to DARE, from which that dictionary incorporates more than 500 items.