Grammar and Syntax of Smoky Mountain English (SME)

(Originally published, in a slightly different form in 2004 in the Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English by Michael Montgomery and Joseph S. Hall, pp. xxxv-lxix.)

Contents

0 Introduction

1 Nouns

2 Pronouns

3 Articles and Adjectives

4 Verbal Morphology

5 The Verb Be

6 The Verb Have

7 Other Verb Features

8 Modal and Semi-Modal Auxiliary Verbs

9 a-Prefixing

10 The Infinitive

11 Negation

12 Direct and Indirect Objects

13 Adverbs and Adverbials

14 Prepositions and Particles

15 Conjunctions

16 Existentials

17 Compound and Complex Sentences

18 Other Patterns

19 Prefixes and Suffixes

0 Introduction

This sketch surveys the elements of morphology and syntax—how words are formed and constructed into phrases and clauses—of the traditional English of the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, one of the most widely recognized parts of Southern Appalachia.1 Its traditional pronunciation has been treated extensively in Joseph Sargent Hall's The Phonetics of Great Smoky Mountain Speech (1942) and its word-stock and semantics presented and illustrated in the Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English (Montgomery and Hall, w004). Much information on grammar appears in the latter work as well, but in piecemeal fashion at separate entries. Organizing the relevant material by traditional parts of speech and other categories permits a broad, synoptic picture of the grammar of SME, as well as attention to contextual details and analytical concerns not permissible in the confines of dictionary entries. Most features of Smokies speech are shared with types of English in nearby regions, but to date its grammar has received little consideration in the literature.2

The presentation here is contrastive: to identify and exemplify differences from “general American English” or “general usage” (terms that do not necessarily imply the existence of an invariant or national norm of American English).3 Such an orientation permits only a limited view of Smoky Mountain speech, and the peculiarities of grammar cited will inevitably appear more numerous and prevalent than would ever occur in a conversation with a typical speaker. Likewise, it can convey the comparative currency of forms only by using such qualifying adverbs as “occasionally” or by specifying the one form among two or more that is the most common. The focus throughout is on structural contrast with general usage. The people whose grammar is presented here live or lived near the Tennessee/North Carolina border in the vicinity of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which encompasses an area roughly sixty miles long by thirty miles wide lying in approximately equal proportion in each state. The 800-square-mile area is itself no longer inhabited. The features presented here were not necessarily typical or used by all or even most speakers in the Smokies. That speakers of any variety fluctuate between forms is true no matter how small the community, as it is usually the case within the individual. The scope of this survey permits only a qualitative view of variation, except for verb principal parts (section 4.2).

Citations have been drawn from recordings, observations, or reports of the speech of the Smoky Mountain area as outlined below, with priority given to examples from recordings reviewed by the author whenever possible. This range of sources produces the fullest account of the subject to date, one that documents the language of rural speakers in the second and third quarters of the twentieth century. They were people of modest formal education living on the land in a largely self-sufficient, agricultural economy.

0.1 Sources

This sketch is based largely on four types of sources:

A) Interviews recorded by Joseph Hall in 1939 and by personnel of and volunteers for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park between 1954 and 1983. These have been audited by the author, who has transcribed and fashioned many of them into a computer-searchable Corpus of Smoky Mountain English (CSME). Hall's early material was drawn from nearly one hundred people reared in the mountains before the displacement brought by the national park in the 1930s.

B) Interviews recorded by Joseph Hall in the 1950s and observations made by him of mountain speech between 1937 and 1987. These materials produced numerous citations for dictionary, but except for a few recordings, they have not been audited by the author.

C) Material recorded by other investigators and reported in the scholarly literature. This includes surveys by the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States and studies of doctoral students, including the author's own work in the Smokies foothills in Tennessee.4

D) Materials not tape-recorded but appearing in printed literature from reputable observers, especially local historians and commentators who were frequently native speakers of Smoky Mountain English. Though not equivalent in status to the first three sources, such materials are invaluable for attesting many infrequent and old-fashioned forms.

1 Nouns. Nouns are notable for the many ways in which their plurals differ from general usage.

1.1 Nouns of measure and weight like mile, pound, and year often lack plural -s when preceded by a numeral or another word expressing quantity. Such usage reflects the partitive genitive in the history of English.

We had to walk ten mile to school.

The bear weighed four hundred and seventy-five pound.

[We] took that hide offen it and cut it into four quarter.

I am nearly ten year older than my brother right over there.

1.2 Nouns interpreted in general usage as mass nouns (and thus unmarked for number) are sometimes construed in SME as count nouns. When this is the case, they may or may not take plural -s or an indefinite article:

Dan Myers has got lots of beards. (i.e. a long, bushy beard)

Sometimes, you know, people would kill a beef or a sheep.

We killed a heap of beeves.

These gravels are hard on your feet.

Have you got any easing powders?

We had several rock on that trail and nothing to drill those rock with.

1.3 On the other hand, a count noun in general usage may be interpreted as a mass noun in the Smokies:

They scattered my plank on the ground. (perhaps by analogy with lumber or timber)

1.4 Some mass nouns and singular count nouns ending in -s or a similar consonant may be interpreted as plural in SME, sometimes producing singular forms through back formation.

How did you go about cutting up that many cabbage?

Give me a hunk of them cheese.

I reckon most of the deal in getting your licen (i.e. a marriage license) is having the three dollars it takes to pay.

We like them molasses.

A panther is more of a dog specie, a lot bigger and way longer than a wild cat.

1.5 Plurals of nouns for animals are noteworthy in two respects. The lack of -s on deer may be extended to other nouns for other game animals:

He hunted coon, deer, [and] bear.

[There are] lots of wildcat here.

On the other hand, -s may be added to nouns that do not take the suffix in general usage:

[There] was deers and bears and all kinds of wild animals, I reckon.

Them sheeps would just eat that a sight in the world.

I caught a mess of trouts today.

1.6 Double Plurals. Nouns that are historically plural in English may be interpreted as singular in SME, taking an indefinite article and producing a double plural form:

We'uns come from educated folkses.

He didn't have a thing on but his galluses and his shoes. (original singular form gallow)

They built a little one-room house and had the Tow String childrens to go to school there a long time.

He was a good hand to break a oxen.

They had milk cows and oxens that they worked.

1.7 In SME nouns ending in -sp, -st, or -sk sometimes preserve the longer plural form -es that is inherited from earlier English:

waspes

Them joistes run through there.

The birds have built nestes in the spring house.

Over on the side of the mountains you will see a little house on stilts or postes.

He'd make [the tobacco leaves] up in these fancy little twistes of tobacco.

Other nouns follow the pronunciation tendency of adding a t after a final s sound (seen in across => acrost), to which the syllabic plural may be then added:

We have both men's and women's clastes.

She taken two dostes of medicine.

1.8 Regularized Plurals. A few nouns irregular in general usage may take regular plural forms in SME (foremans, gentlemans, womans). In religious discourse sister is occasionally pluralized as sisteren, by analogy with the more general brother/brethren.

1.9 Associative Plurals. In Smokies speech the phrases and all, and them, and and those mean “and the rest, and (all) others” and are used after a noun to include associated people (i.e., group or family members) or things.

I carried roasting ears, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, and all.

Pap and them was a-carrying the bear.

Helen and those were there.

2 Pronouns

2.1 Personal Pronouns. The nominative and objective forms of personal pronouns brhave for the most part as in general American English, with the most noteworthy exception of you’uns (for you ones), you all, and y'all in the second-person plural and hit in the third-person singular.

Nominative Case

Singular / Plural

1 I, me / we, we'uns

2 you, ye / you, you'un, you'all, y'all, you all, ye

3 he, him / they

she, her

hit, it

Objective Case

1 me / us

2 you, ye / you, you'uns, you'uns all, y'all, you all, ye

3 her, him, hit, it / them

Objective forms of personal pronouns occur as indirect objects, direct objects, and objects of prepositions. In the 1930s Hall observed a few illiterate speakers using single objective pronouns in subject position, as in the following, but these do not appear on any recordings. However, the objective pronoun is often employed in subject position when conjoined with another pronoun or with a noun (in the latter case the personal pronoun usually comes first). This pattern with plural pronouns is very rare.

So me and four cousins began right then and there to lay our plans to go.

My daughter and me went over there.

Uncle Jim used to come up to home and me and him would bee hunt.

Her and Jess and the girl is all buried there on Caldwell Fork.

Him and one of his nephews went a-fishing one time, and they was up on what was called Desolation.

That mine you and Tom Graves found, how can you go to it?

2.1.1 First Person and Second Person Pronouns. We'uns may occur in the Smokies, but it is far less common than another form based on ones, you'uns (usually pronounced as two syllables). In Hall's observations you'uns occurred in traditional, familiar speech, whereas you all was more formal and used by better educated speakers. Though it remains current and is the traditional periphrastic form in mountain speech, you'uns has been giving ground to you all (and less often to y'all) for at least two or three generations.

We'uns come from educated folkses.

You'uns set in front.

You all may be need[ing] it one of these days.

Y'all come back.

Ye (pronounced [yi] or yi] is a variant pronunciation of you, not a retention of the Early Modern English plural ye as found in the King James Bible and elsewhere. It occurs in both the singular and plural, usually in unstressed positions, as a direct object, an object of a preposition, or a subject when inverted in questions. It may also appear as a reflexive pronoun.

[Boneset is] bitterer than quinine, and hit'll kill ye or cure ye one.

If you call [a turkey] too much, you'll never get one to ye.

You can see the ski lodge yander, can't ye?

How old was ye?

Get ye chairs.

2.1.2 In the third-person singular, hit (the older form of the pronoun) alternates with it, occurring most often in stressed positions (usually as a subject) and less often elsewhere.

Stressed:

Hit's been handed down to him, you see, so he's the third or fourth generation.

Hit must have been in the thirties, in the twenty-nine, because I was up there on that river about eighteen year.

Unstressed:

I don't know how long hit's been.

They had to raise the young one and take care of hit.

Singular Plural

1 my, mine our, ours, ourn, ournses

2 your, yours, yourn your, yours, yourn, your'unses, you'uns

3 his, hisn their, theirs, theirn

her, hers, hern

its, hits

In attributive position possessive pronouns conform to general usage with only occasional infrequent exceptions like the following:

That dog done hits best to break loose.

I taken you'uns potion, for I had a misery.

In absolute or disjunctive position (e.g. at the end of a phrase or clause) possessive pronouns formed with -n (hern, hisn, etc.) rather than -s sometimes occur. Historically these developed by analogy with mine and thine, but many speakers today take them as deriving from a possessive pronoun + a reduction of own or one).

The white mare is hern.

I don't know just how he made hisn.

[We] generally sold ourn to a man on Coopers Creek.

The colts is theirn.

Work them just like they was yourn.

What did you'uns do with yournses?

Singular Plural

1 me, myself us, ourself, ourselfs, ourselves

2 you, ye, yourself you, ye, yourself, yourselves, you'unsself

3 him, himself, hisself

her, herself them, theirself, theirselves, themself

it, itself themselfs, themselves

Reflexive pronouns in Smokies speech differ from general usage in four ways.

2.3.1 In a construction often known as the personal dative, personal pronoun forms are used rather than forms in -self/-selves, especially with the verbs get and have.

Git ye chairs. (singular or plural)

George built him a house up there.

I had me a pair of crutches.

They'd get them out honey.

We had us a big fire made up at the root of the tree.

Mary is fixing to make her some cotton dresses.

2.3.2 Plural reflexive pronouns are sometimes formed with -self or -selfs, in addition to -selves.

We built another little barn ourself.

We went by ourselfs to the head of Forneys Creek and fished.

I said, “Dang you ones. If you want them out, get in and get them yourself.”

Step up here, boys, and he'p you'unsself.

They'd all go and enjoy themself.

I like to see young people try to make something of themselfs.

I've done forgot what they call theirself.

2.3.3 Following the pattern of myself and yourself, third-person reflexive pronouns sometimes add -self or -selves to a possessive rather than an objective form of a personal pronoun:

The little boy stayed there all night by hisself.

I've done forgot what they call theirself.

They even carded the wool theirselves.

2.3.4 Own is sometimes added to form an emphatic reflexive, which is always based on the possessive rather than the objective form.

Now that was an experience I experienced my own self.

They could prove you took a hand in it your own self.

He has a little kit to give his own self a shot.

Everybody took care of their own self.

People doctored their own selfs.

Most of them were blockaders their own selves.

Singular Plural

this, this here, this here’un, this’un (this one) these, these here

that, that there, that’un (that one) them, them there, those

yon/yan yon/yan

yonder/yander yonder/yander

These forms are used as demonstrative pronouns (and usually also as demonstrative adjectives) in SME. As in traditional English elsewhere, the distinction between proximate, intermediate, and distant is maintained (this vs. that vs. yon). Yon/yan and yonder/yander most often function as adverbs (see §13.4), but you and yan may also be demonstrative adjectives. A speaker who employs the three-way distinction may be able to express a further degree of physical and conceptual distance more economically than those with the two-way distinction. As in many other varieties of English, them occurs as a demonstrative pronoun and adjective in the Smokies. This and that and their plural forms may combine with here, there, or ’un.

Demonstrative Pronouns:

Them's not perch, them's bass.

This here's the old residenter bear hunter, Fonze Cable.

This here’un was made out of metal, you know. It had a lid, a little lever.

Maybe this'un had preaching first, and then they'd have Sunday school.

These here was on the inside there.

That there's Tom's boy, I guess.

We'll try another'un, being that'un paid off.

Demonstrative Adjectives:

Middlesboro is on yan side of Cumberland Gap.

You cross the big bridge going in yander way right there.

I'm afeared of them copperheads.

This here beadwood bark, make hit for tea.

He had one of these here hog rifles.

That there sawmill I worked at was there before I married.

Them there fellows come through here, stealing horses and things.

2.5 Indefinite Pronouns. Notable usages of indefinite pronouns in the Smokies include ary/ary'un, nary/nary'un (see §3.2) and the singular indefinite form a body.

We decided we’d go back in the sugar orchard to see if ary’un had come in there

We didn’t see nary’un.

Could a body buy that there dog?

A body thought about it back then.

2.6 Interrogative pronouns, used to introduce direct or indirect questions, are noteworthy in several regards. SME has a set of forms that invert ever and the wh- element (see also §15.1).

We'll do everwhat Jim wants to do.

Everwhich one come nigh always come down to the house and stayed full half the night.

Everwho hears that will be surprised.

Interrogative pronouns may be combined with all in who all, what all, etc. (§2.7.2).

2.7 All. As suggested in §2.1, all can combine with other forms, usually to express inclusiveness. In these cases all takes secondary stress, making the constructions compounds rather than phrases.

2.7.1 Combining forms include personal and possessive pronouns (they all, you all, your all, theirs all, and you'un(s) all); in all of these the stress falls on the first element, not the second. Of these compounds, you all is the only one to have acquired properties of a personal pronoun).

Cades Cove nearly took theirs all to Gregory Bald.

It all doesn't mean anything.

Old man Lon and Will all, they all went with him.

You-all may be [needing] it one of these days.

Is this table your all's?

I want you'un all to come out to church next Sunday.

They'll catch you-uns all.

2.7.2 More often, all is combined with an interrogative pronoun to convey the inclusiveness and generality of a query or statement. Thus, who all is equivalent to both “all of whom?” and “who in general?”

I don't know where all he sold it at.

I don't remember all how we used it.

What all kinds of herbs do you have on your porch?

I can remember what all happened, but I can't remember how old I was.

Who all was there?

Occasionally all is placed after a noun for the same reasons.

They'd shear the sheep, and she'd spin the wool, the thread, and make our britches and our shirts all.

2.8 One. The indefinite pronoun one is frequently contracted and reduced to ’un (occasionally ’n) when it is unstressed and follows a pronoun (§2.1) or an adjective.

We’uns can say nigh of two hundred would come a heap closer.

You'uns is talking about rough country.

We'll try another'n, being that'un paid off.

The gooder'ns's all gone now!

This here'un is made out of metal.

What one didn't have another'n did.

Jack is an old hand to coon-hunt, but he never catches nary'un.

I don't recollect any of his young'uns.

They's all sizes from little'uns to big'uns.

If he killed ary’un, it was before my recollection.

(See §18.1 for one following or in coordinate constructions.)

2.9 Relative Pronouns. In Smokies English at least nine forms are used to introduce a relative clause (that, who, i, ’at, which, as, what, whose, thats). All of these are used in restrictive clauses, with that being far more common than any other form regardless of whether its head noun is human or non-human. Nonrestrictive clauses, less frequent than restrictive ones, are introduced by which, who, or that. In addition to whose, thats is attested as infrequent possessive form, but is extremely rare. Contrasting with general usage are the following:

That (either restrictive or non-restrictive):

Human Head Noun, Non-Restrictive Clause: Mister Wilson Queen, that lived there at the campground, he was a song leader when I was a little girl.

’at (reduced form of that, only restrictive):

Non-Human Head Noun, Restrictive Clause: And we had some old trained bear hounds 'at turned off in the roughs.

i:

The ellipsis of a pronoun (i) occurs only in restrictive clauses and most often in existential constructions (see also §16.3). Unlike in general usage it may represent the subject of the verb in the relative clause.

Human Head Noun: He was the crabbedest old feller i ever I seed.

Human Head Noun: He come up to a party i had been a-fighting a bear.

Non-Human Head Noun: They was two wagon loads i went out from there.

which:

Human Head Noun, Non-Restrictive Clause: Then he handed it down to Caleb, which was Eph's pa.

as (only restrictive):

Non-Human Head Noun, Restrictive Clause: They would mind rather than to take the punishment as I would put on them.

Human Head Noun, Restrictive Clause: Tom Sparks has herded more than any man as I've ever heard of.

What (only restrictive). The relative pronoun what, common in literary portrayals of mountain speech, is virtually non-existent in speech; Hall, for example, collected only one example of it.

Human Head Noun, Restrictive Clause: I knowed the White Caps what done the murder.

thats “whose” (only restrictive)

Human Head Noun, Restrictive Clause: We need to remember a woman thats child has died.

3 Articles and Adjectives (for demonstrative adjectives, see §2.4)

3.1.1 The indefinite article a [!] rather than an is often used before nouns beginning with a vowel sound in SME. Often it is partially absorbed by the following vowel.

We used to have a organ, and we don't have it there anymore.

[It] maybe might have been a epidemic of whooping cough or measles or something like that.

Just go on up to the Pole Mountain till you come to a ivy thicket.

3.1.2 In Smokies speech the definite article is employed in several notable contexts.

in place names: the Smoky (= the main ridge of the Smoky Mountains), the Pole Mountain.

in the phrase in the bed.

with superlatives: the best “very well” (as “I always thought they got along the best”).

to indicate possession: the old lady “my wife,” the woman “my wife.”

with an indefinite pronoun: the both, the most.

with names of diseases and medical conditions: the fever “typhoid,” the sugar “diabetes.”

Before other(s) the definite article is occasionally reduced to t', producing t'other(s). With the function of t' as an article having been obscured, t'other may itself be modified by the.

One or t'other of them whupped the other one.

When one's gone the t'other's proud of it.

3.2 Indefinite Adjectives (see also §2.5). Ary “any” and nary “not a one, not any” occur in declarative clauses (occasionally in interrogative and conditional ones) and sometimes take an enclitic 'un (< one) to form the indefinite pronouns ary'un [Uær!!n] and nary'un [Unær!n]. Originally derived from e'er a (from ever a) and ne'er a (from never a), ary and nary in mountain speech preserve the adjective function of these constructions. According to Hall's observations in the 1930s, ary and nary were somewhat more emphatic than any and none and more likely to refer to singular things or units than to plural ones.

We didn't kill ary deer then.

We never seed nary another wolf.

If he killed ary'un, it was before my recollection.

I never seed a deer nor saw nary'un's tracks.

3.3 Comparatives. In the Smokies the comparative form of adjectives occasionally differs from general usage.

Nothin' [is] gooder than crumbled cornbread and milk.

You're nearder to the door than I am.

Double comparatives such as the following are characteristic of Smokies speech:

I'd say I was more healthier back then than I am now.

I was getting closer and more closer with every step I took.

I think there are worser things than being poor.

3.4 Superlatives. Double superlative forms also occur in Smokies speech.

Newport, though, is one of the most liveliest towns that I know of.

Doc was the most wealthiest man [in] this part of the country for to buy at that time.

The superlative suffix -est is sometimes added redundantly, including on adjectives that are historically superlative or absolute.

She could make the bestest [sweetbread] in all the country, we thought.

Who got there firstest?

Who got there secondest?

Who growed the mostest corn?

The superlatives suffix -est may be added to adjectives of two or more syllables that in general speech take the modifier most.

Tom Barnes was the completest hunter I was ever acquainted with.

He's the disablest one of the family.

All my family thought that was the wonderfullest thing ever was.

3.4.1 In Smokies speech present participles of verbs used as attributive adjectives sometimes take the superlative suffix -est.

That's the cheatin'est place at the fair!

Daddy said he was the gamest and fightingest little rascal he ever hunted.

These are the singin'est children I have ever seen!

Ad said Barshia was the thinkin'est boy in the world.

He had told somebody she was the workingest girl in the country.

She’s the aggravatin’est calf I’ve ever had .

Some of these forms have more than one possible interpretation. To say that someone is “the workingest” person ever seen may mean that person works very long (“the most”), very well (“the best”), or very hard. Likewise, singingest can be paraphrased as “sings better than anyone else,” “enjoys singing more than anyone else,” or “sings more than anyone else.”5

For best “most,” see §13.2.

3.5 Anomalous Comparatives and Superlatives. In Smokies speech a form of big together with the noun it modifies is equivalent to most. Big may appear in its positive, comparative, or superlative form and modify any of several nouns, but the meaning of the construction remains the same (“most” or perhaps more loosely, “major”).

A big majority of the people went to church pretty regular.

My father did the big part of the farming.

They done the bigger majority of their logging on Laurel Creek.

He rode a horse the bigger part of the time.

The biggest half of the people does it.

The biggest majority down there, they care.

[The county] went Democratic, biggest part of the time.

[The] biggest portion of people didn't have lumber.

Other unusual superlative forms include onliest “only” and upperest “situated on the highest ground, farthest up” (from upper “on high ground”).

She treated it as if it was the onliest one she had.

Turkey George Palmer was in the upperest house on Indian Creek.

3.6 All the. The adjective phrase all the has the sense “the only” (as in general usage), but in addition to mass nouns it can modify singular count nouns or the indefinite pronoun one.

It was just a sled road but it was all the way you could take anything up there.

I reckon that's all the name she had.

That's all the one they got here.

All the can also modify the positive, comparative, or superlative form of an adjective to express extent.

That's all the far I want to go. (= as far as)

This is all the further we can go. (= as far as)

Is that all the best you can do? (= as good/well as)

4 Verbal Morphology. Verb inflections in Smokies English to mark agreement and tense are usually the same as in general usage in form, but they are often used in different contexts and follow different rules.

4.1 Subject-Verb Agreement. In his notes from the 1930s Joseph Hall observed that less-educated speakers used -s outside the third-person singular (as “if you wants to go”; “I knows them when I sees them”; “they says he done it”) and that -s was in some cases absent from the third-person singular (as “Who want to know?” and “He still do live here”). However, such usages do not occur on his recordings or in other sources. Verbs in the third singular conform to general usage in nearly all respects. The most common exception is don’t in the third-person singular. Occasionally it seems appears as seem, with the subject pronoun omitted (“Seem like I've heard it”), Verbs ending in -st sometimes take a syllabic suffix (parallel to nouns, shown in §1.7).

That water freezes on the bark and bustes [i.e. bursts] it.

Hit costes too much.

It disgustes me now to drive down through this cove.

For subject-verb agreement the principal difference between Smoky Mountain English and general American English lies in third-person plural contexts. In these, -s occurs frequently on verbs having any subject other than a personal pronount (as in people knows, some goes, etc.), but very rarely with the pronoun they (except when expressing the historical present, §7.4). This pronoun vs. non-pronoun pattern follows a rule that can be traced to Scotland as far back as the fourteenth century and that operates as well for the verbs be and have.6

They settled up there and entered all that land up back across the river over there where Steve Whaley and them lives.

This comes from people who teaches biology.

Some thinks it might be a mineral that causes it.

It's where people gathers up and shucks corn in the fall when they get the corn gathered.

That's the way cattle feeds. They feed together.

A pattern following the same rule involves verbs with a personal-pronoun subject not adjacent to the verb. This pattern is attested in old letters written from the Smoky Mountains, but apparently did not survive into the twentieth century:

I am very glad to hear that you have saved my foder and is doing with my things as well as you are. (1862 letter)

We have some sickness in camp of mumps and has had some of fever. (1862 letter)

I am now Volenteard to gow to texcas against the mexicans and Expecks to start the last of September or the first of October. (1836 letter)

For use of the suffix -s to express the historical present, see §7.4.

4.2.1 Regular Verbs. Parallel with the noun plural and verbal agreement suffixes (§1.7 and §4.1), a syllabic variant of the tense suffix is occasionally added to verbs ending in -st when general usage does not.

It never costed me one red [cent].

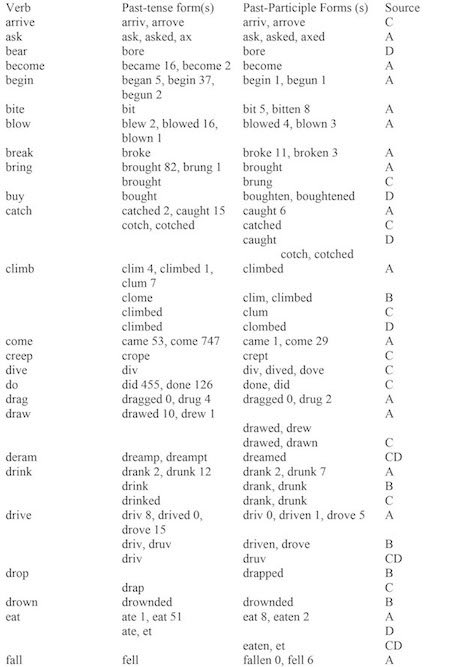

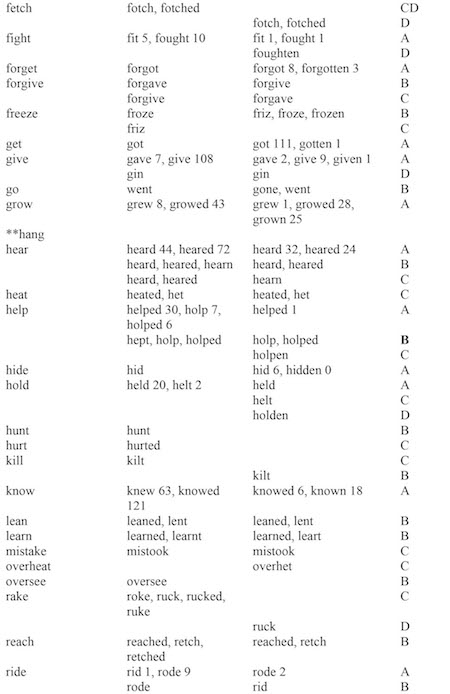

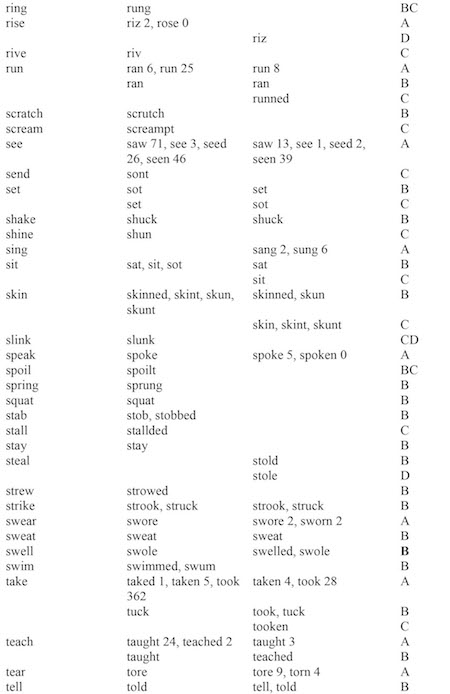

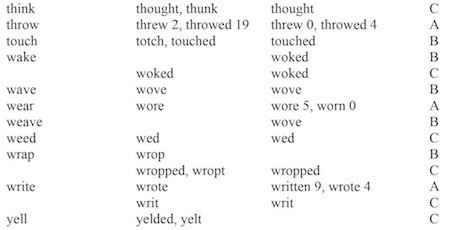

Smokies English exhibits much variation in the principal parts of both regular and irregular verbs. Verbs that are regular in general usage are often irregular in the mountains, and vice versa. More often verbs are irregular in both varieties but differ in their past-tense or past-participle forms. The table below identifies verbs whose principal parts vary in SME. Where variation occurs in the Corpus of Smoky Mountain English, the frequency of each form is indicated for the CSME, in order to present a quantitative view of this important area of grammar. At the same time, for each verb the type of source (identified at the introduction earlier as A, B, C, or D) in which each form is attested is indicated. Gaps in the list indicate that no form occurred in the material consulted, not that one is not found in speech.

The nearly one hundred verbs listed above vary considerably in their patterning, but most variant forms are centuries old and traceable to Early Modern English, if not earlier. Many may be usefully grouped according to how their past tense is formed.

4.2.2 Verbs with Variable Irregular Forms. In some cases (e.g. climb, help) older, irregular past-tense and past-participle forms have tended to be replaced by regular forms more slowly in SME than in general usage. In other cases (e.g. took) one irregular form has tended to dominate in SME for both the past tense and past participle.

begin, began/begin/begun, begin/begun

climb, clim/climbed/clome/clum, clim/climbed/clombed/clum

come, came/come, came/come

do, did/done, did/done

drink, drank/drunk, drank/drunk

drive, driv/drived/drove/druv, driv/driven/drove/druv

eat, ate/eat/et, ate/eat/et

give, gave/gin/give, gave/gin/give/given

run, ran/run, ran/run

take, taked/taken/took/tuck, taken/took/tooken/tuck

4.2.3 Some verbs that are irregular in general usage have both irregular and regular forms in SME.

blow, blew/blowed, blowed/blown

catch, catched/caught, catched/caught

draw, drawed/drew, drawed/drawn

grow, grew/growed, growed/grown

know, knew/knowed, knowed/known

see, saw/seed, seed/seen

teach, teached/taught, teached/taught

throw, threw/throwed, throwed/thrown

4.2.4 Some of the verbs in §4.2.2 have been leveled almost entirely to one form in traditional SME.

come, come, come eat, eat, eat

give, give, give run, run, run

4.2.5 Regular verbs that have lost their -ed suffix (perhaps by analogy with put/put/put, etc.) include hunt and squat.

We hunt one night up on Scratch Britches Mountain and dark come along.

They moved out and come on up here and squat up there in Gatlinburg.

5 The Verb Be

5.1 Inflected forms of be in the present tense indicative.

Singular Plural

1 am, 'm, 's (once) are

2 are are

3 is, are are, is

There are no instances of we is or you is in the sources, and only one of I's (contraction of I + is, in “I’s diggin’ seng right now”). Thus, of inflected forms in the present tense, only those in the third person require discussion. In the third singular, are occurs occasionally in existential clauses having a singular subject:

They are another one down the street.

It seems like they used to be more water in the streams than they are now.

In the third-person plural, variation between are and is follows the subject-type rule discussed for other verbs (§4.1).

The bears is getting very gentle.

The rocks is still there yet.

With the expletive there (commonly pronounced they), is or ’s generally prevails whether the following subject of the clause is singular or plural:

There's lots of mountains.

They's about six or seven guitar players here.

5.2 Uninflected be. Although frequently employed by writers of fiction set in the mountains, finite, uninflected be in main clauses has been obsolescent in Smokies speech since the early twentieth century, if not earlier. It was not observed by Joseph Hall in the 1930s or later. When it occurs, be does not express habitual or repeated actions as in African American English. It is found most often in subordinate clauses introduced by if, until, or whether, contexts that are historically subjunctive.

If it be barn-cured tobacco, you have a different thing.

He would ... leave [the tobacco] until it be so hard when it would come out it would never get dry and crum[b]ley.

... whether it be just providing materials so that you wouldn't have to ship cargo from way off.

Finite be also occurs in main clauses, regardless of the number and person of the subject.

Many be the time ...

Them be all right to ride in, but you'll find out they ain't good to hike in.

I be too old for such tomfoolery.

Be you one of the Joneses?

5.3 Past Indicative Forms of be.

Singular Plural

I was, were we was, were

you was, were you was, were

he/she/it was, were they was, were

In traditional Smokies speech, was and were may be used for either singular or plural, but there is today and has long been a strong preference for was in all persons and numbers. The use of were in the singular has a historical basis in the dialects of southern England, but its use in the mountains may be due in part to speakers who no longer distinguish between was and were in the plural and fluctuate between the two in the singular from insecurity.

I stayed there from the time I were about fifteen years old.

There weren't even a sprig of fire in his place! The fire were plumb out.

The moon were shining bright.

He weren't no hunter neither.

Was occurs frequently with plural subjects of all types:

They come from Ireland. They was Scot Irish.

You had to work the roads six days a [year] after you was twenty-one years old.

We was poor folks and hired out [to] get enough money to buy cloth to make me a dress.

The older people was inclined that way.

Was is occasionally contracted with I to form I's or with they or there in existential clauses.

I knowed I's a new duck.

They’s two coons up the tree. We shot them out,

5.4 Negative Forms. In negative clauses contracted forms of am, is, and are are the norm in SME, but patterns with negation vary from general usage in several ways. The verb form may contract with either the subject (“He's not”) or with n't (“He isn't”; see §11.6). In all persons and numbers ain't is a common alternative to forms of be in the present tense. Hain’t also occurs, Especially but not exlusively at the beginning of a clause.

With ten brothers and sisters, he ain't a gonna get lonesome.

It ain't half as big as it used to be.

Hain't no use to tell you anything about my sickness, Dr. Abels. I ain't got no money.

They hain't a-going to do that.

To negate a verb, don't is occasionally added to be, especially in an imperative clause with a following progressive verb form.

Don't be a-takin' it down till I tell you a little.

Don't be wearing your good clothes out to play in.

6 The Verb Have

6.1 Inflected forms of have in the present tense parallel those of be. Have occurs in the third singular, but rarely and apparently only in existential clauses.

They've been a big change.

In the third-person plural, variation between have and has follows the same variable subject-type rule for other verbs (§4.1) and for be (§5.1). Has is often used with plural nouns, but not with they.

The young folks has left that place.

They actually have folks here ... some of them has their grandmother and grandfather.

6.2 Perfective uses. In Smokies speech has been frequently occurs with adverbials that take the simple past tense in general usage, especially phrases having the form ago.

It's been twenty year ago they offered me a house and land.

This has been along back just a few years ago, before the park took over the Hazel Creek boundary ...

That's been a way back yonder.

It's been a good while back, because I read it.

In the Smokies have and had are sometimes separated from their past participle by a direct object.

After we had all our work done up and eaten a good camp supper, I told Mark let's organize for the hunt tomorrow.

6.3 Infinitives after have, see §10.3.

6.4 Negative Forms. In negative contexts have and has may be contracted to their subject. Alternatively, a contracted not may be attached to the verb form (“She's not” or (“She hasn't”; §11.6). In all persons and numbers ain't is a common alternative of have in the present tense, and it occasionally occurs in the past tense. Especially but no exclusively at the beginning of a clause, the variant hain't sometimes occurs.

It's not been very lucky to get railroads there.

You've not met him, I don't guess.

I ain't seen nothin' of him.

It ain't been long ago.

They hain't found it yet.

Hain't nobody never set it for any bears since; that's been thirty years ago.

6.5 Deletion and Addition of have. Auxiliary have and had are sometimes elided in Smokies speech, especially before been or between a modal verb and a past participle. This pattern is based in part on phonology. See also §8.2.

(Q: How you getting along now?): A: I i been a-farmin' a little along.

I was done supposed to i been there.

You ought to i seen us all a-jumping and running.

He must've died in the forties. It must i been forties whenever he died.

You wouldn't i ever thought about kids a-comin' out of them hollers and hills.

Have of ’ve may occur as a superfluous form in conditional clauses (perhaps by analogy with would).

Had that not have happened, there would have been somebody come in here with a lot of money.

I wish I had’ve kept all my old books

7 Other Verb Features

7.1 Progressive forms are frequently employed for stative verbs of mental activity, especially want, in the process giving the verbs a dynamic interpretation.

Was you wantin' to go to town?

That's not what I was a-wantin' to hear.

We was liking you just fine.

Present participles frequently take the prefix a- (§9).

7.2 Perfective Aspect. To express completed action, sometimes to stress that completion, did or done is often used. In negative clauses did usually occurs with an infinitive form and with n't (as in general English), but sometimes with never (thus,”I never did see” = “I have never seen” or “I never saw”). The emphasis of such constructions is shown by the stress placed on each of the words never and did, sometimes also with the following verb and other verb phrase elements.

I never did see Grandma do any work of any kind.

I never did know what caused it.

I never did live in a place where they was no meetings or no singings.

Auxiliary done expresses completion and is roughly equivalent to “already,” “completely,” or both. It most often precedes a past participle and may be accompanied by a form of have or be. Occasionally it is followed by an adjective, an adverbial, by and, or by a past-tense verb.

I already done seed three.

We stayed there till the bears done eat all the honey.

He got a job there hewing cross-ties for that railroad, as I've done said.

We thought pa and ma had done gone to church.

Herdin' was done stopped before the park come in.

The older ones was done through school and married.

Uncle John Mingus was done dead.

She's done and brought her second calf.

7.3 Ingressive or Inchoative Verbs. The beginning of an action or an action just begun may be expressed by any of several constructions involving a verb followed by an infinitive or verbal noun. or . While these are generally equivalent to “begin” or “start,” they may vary in their nuances, some indicating one action followed immediately by another. Some are no doubt pleonastic, but others make action more graphic and vivid and are commonly used in story telling.

begin to + verbal noun: Then next day everybody begin to wondering what caused the blast to go off.

break to + infinitive: It was a bear a-coming, and so he broke to run.

come on to + infinitive: I went in the house when it come on to rain.

commence to + infinitive: I commenced to train a yoke of oxen.

commence to + verbal noun: He went back up to the tree and commenced to barking.

fall in to + verbal noun: Mr. Huff said to me, “Wiley, fall in to eating and eat plenty, for you boys may haf to stay out all night.”

fall to + verbal noun: I fell to shooting [the bear] and shot him ten times then before I killed him.

get + verbal noun: He said them men got hollering at him, and he give them a pumpkin.

get to + verbal noun: They got to deviling us about sparking; Later on the Indians got to burying their dead east to west.

go + verbal noun: He'd just get a little out of his bottle and just go putting that on there.

go in to + verbal noun: We just broke to it as quick as we could, and all went in to skinning that bear.

go to + verbal noun: One night he heard that hog go to squealing and hollering.

let in to + verbal noun: Then he let in to fussing at me because I let her go over there to spend two weeks with Amy.

set in to + verbal noun: Hit set in to raining about dark.

start in + verbal noun: Brother Franklin started in telling stories.

start in to + infinitive: I got so I started in to read it by heart.

start in to + verbal noun: So we started in to fishing near the Chimney Tops.

start off to + verbal noun: They started off to hunting.

start to + verbal noun: Then we'd all start to shelling [the corn].

take + verbal noun: He made a dive at my brother Richard, and he took running off.

take to + verbal noun: I was hoein' my field beans when somebody tuck to shootin' over in the pine patch.

7.4 Historical Present. In the recounting past events, especially in narrative style, a speaker may vicariously shift closer to the action by adding -s, usually to say.

They comes back and Scott says he was a-coming over to their house when Lester come back.

She turned over against the wall and she says, “Lord, let me live.”

I thinks to myself I'll just slide down there and see if he'd make me holler.

So she gets up and started to go around the house to look for him to tell him what she thought.

8 Modal and Semi-Modal Auxiliary Verbs

8.1 Modal verbs. Except for mought, an obsolescent variant of might6 (“They mought have done it”; “That mought be what makes them so sour”), modal auxiliaries in Smokies speech differ from general usage only in usage, not in form. As in other Southern varieties of American English, might or sometimes may (rarely another modal) may combine with another modal to express possibility or condition on one hand and indirectness (and thus politeness) on the other. These “double modals” tend to occur in certain types of face-to-face interactions, when one person is proposing or arranging something with another.

One of them might could tell a man where her grave is at.

If you give me thirty minutes, I mighta coulda thought of some names.

We finally decided we might ought to stop and ask at a service station.

I might can go with you tomorrow.

They say I could might have lived to make it to the hospital.

Used to can combine with a modal verb or another auxiliary.

The drummers would used to come from Morristown.

You used to could look from Grandpa's door to the graveyard and the church house where we attended church.

We used to didn't have nearly so many houses.

The children used to would kind of stay in the background.

8.2 Semi-Auxiliary Verbs. In the Smokies several phrases occur in a fixed position before a verb and modify the principal action or statement of the verb. These include older forms such as liked to and such American innovations as fixing to. Some phrases can be inflected for tense, but others are more adverbial in their properties.

belong to “to be obligated or accustomed to, deserve”: That train don't belong to come till 12:15; He belongs to come- here today.

fix to/fixing to “to prepare or get ready to, be about to, intend to”: The base form of the phrase (fix to) is the source for the progressive, but has become recessive while the latter has achieved wide currency in the Smokies and throughout the southern United States.

I fixed to stay a week to bear hunt.

Better fix to come with us.

I'm fixing to leave now.

He looked around and he saw a large panther a-laying on a log fixing to jump on him.

It was a-fixin' to come a storm.

like(d) to “almost, nearly” (originally had liked to or was like to followed by an infinitive form, often have). In Smokies speech today there is usually no evidence of a following have and often only the vestige 'd of preceding had. The final consonant of liked is normally elided with the following to.

He'd like to tuck a hard fit. (= He almost had a violent fit of anger.)

I like to have bled to death.

I stayed in the tree all night and liked to froze to death.

I like to never in the world got away.

He was the mayor the year they like to went broke down there.

need (followed by a past-participle form):

They started before sunup and worked to after sundown, if you had a job that needed finished.

There were men and women living in the Sugarlands with talent and the ability to do most anything needed done in the community.

That thing needs washed.

He'd bring that old jack that needed shoed, you know, and he was hard to shoe.

up and “suddenly, immediately”: They didn't up and take me and run to the doctor; I got to thinking maybe she didn't know it, so I upped and told her that night.

used to “formerly” (in combination with could, did, would*, etc.). See §8.1.

9 a-Prefixing. A prominent feature of traditional Appalachian English is the prefixing of a-, especially on present participles of verbs. Historically this form usually derived from the preposition an or on.

Today the prefix is only a only a relic without meaning of its own, but it may lend a slight dramatic effect in story-telling, which it may occur in a series. The prefix is also well known in ballad lyrics.

It just took somebody all the time a-working, a-keeping that, because it was a-boiling.

I got out there in the creek, and I went to slipping and a-falling and a-pitching.

The prefix occurs on verbs of all semantic and most structural types, as on compound verbs and on verbs in the middle voice (i.e. active verbs whose subjects receive the action).

Way back I guess forty year ago, there was a crowd of us going up Deep Creek a-deer driving.

People will up with their guns and go out a-rabbit hunting, a-bird hunting.

... while supper was a-fixing.

Something happened to the child when he was a-borning.

Much less often the prefix occurs on a past-tense or past-participle form of a verb (this form of the prefix has a different historical source from the use on present participles).

I just a-wondered.

You were a-scared of that place.

I would get them [=oxen] a-gentled up, and then I put the yoke on them.

The prefix may occasionally appear on a preposition, adverb of time or place, adverb, or adjective (see §14.2).

10 The Infinitive

10.1 for to. In Smokies speech an infinitive is sometimes introduced by for + to when general usage has only to. In some cases (especially after like) this construction has an intervening noun that functions as the subject of the infinitive. In others the verb introduced by for to has the implied subject of the higher clause, in which case it usually expresses a purpose and is equivalent to “in order to.”

I’d like for you to give me help here whenever your time allows.

I sent them up here to serve a warrant on you, and I mean for it to be served!

I had to pick sang and pick up chestnuts for to buy what we had to wear.

Little River got to wanting the cables for to take to skid with ’em somewhere.

Doc was the most wealthiest man [in] this part of the country for to buy at that time.

They’d turn the sap side up and they'd use that for to spread the fruit on.

He's lookin' for to quit.

10.2 An apparently recent, American development of the infinitive is its use to express the “specification” or respect in which something is true. This type of infinitive follows certain nouns or adjectives. When it follows an adjective (e.g. “He was bad to drink”), the subject of the higher clause expresses as the subject of the infinitive. The use of bad and awful + infinitive often, but not always, implies unfavorable judgment on the part of the speaker, i.e. that a person spoken of has an

unfortunate, excessive, or undesirable habit, inclination, or tendency.

He was awful bad to drink. (= He was a hard drinker.)

He was a bad man to drink. (= He was a hard drinker.)

[Bears] were bad to kill sheep, but not so bad to kill the hogs.

She was the worst I've ever seen to tell stories.

He's awful to tell stories.

The Queen family was all of them good to sing.

She's an awful hand to fish. (= She's crazy about fishing; she fishes a lot.)

He was no hand to hunt. (= He didn't like to hunt, he was a poor hunter.)

10.3 Infinitives with have. An overt infinitive with to can follow have and its direct object, to express either causation or the occurrence or experiencing of a process or condition.

They'd make sassafras tea, you know, and have us to drink it.

He had my uncle to make a road.

I'd have my mustache to freeze till I couldn't hardly git my breath.

We had a little white dog to go mad.

10.4 Elliptical Infinitives. Want is often followed by a preposition and has an elliptical infinitive, as want (to get, go) in, want (to be) out.

All I wanted out of it was a little bucket of honey.

That dog doesn't know whether he wants in or out.

11 Negation

11.1 Multiple Negation. The negative markers never, no, and not/n’t may occur in the same clause with other negative forms (none, nary, nothing, etc.) or followed by other words of negative value such as hardly in the same clause. Redundant negation is natural in English, having roots in Old English and being found in every stage of the language and in all vernacular varieties.

They ain't a-bitin' to do no good.

I've not never heared of that.

I hain't seen nothing of him.

Did he not get none of it?

Hit didn't scare me nary a speck nor a spark.

The snow never hardly got off the ground.

They [=there] wasn't hardly any at all.

11.2 Negative Concord. Smokies speech generally follows the rule of negative concord, whereby all indefinite elements in a clause with not or never conform in being negative.

We didn't have no use for it noways.

We ain't starvin' none.

There's an old house up here, but don't nobody live in it, not noway.

They wasn't never nobody moved back down there.

None of us wasn't real singers nor nothin' like that.

He wouldn't never charge nobody a dime for nothing like that.

However, there are occasional exceptions to this pattern:

I never did go hardly any.

I never did see Grandma do any work of any kind.

We ain't got any mill at all in there any more except a little hand mill.

11.3 Never. Smoky Mountain English uses never in two ways differing from general usage. First, the form can negate a past-tense verb referring to a single event or an event having a definite stopping point. Thus, never saw and never seen are equivalent to “didn't see,” and Smokies speech has an alternative to the general English pattern of inserting did to negate a verb in the simple past tense, for a one-time, punctual event.

We never seen it then.

I never saw him while he lived.

[We thought] we'd a got all of them [=the bears], but we never done it.

She never died then.

In another pattern, never is followed by did and the base form of a verb. Thus, never did see is equivalent to “didn't ever see,” “never saw,”or “have/had never seen.”

I never did live in a place where they was no meetin's nor singin's.

I never did see Grandma do any work of any kind.

I never did know what caused it.

11.4 As in general usage, nor follows neither in correlative constructions (neither ... nor), but in SME it also occurs without neither. Nor may conjoin clauses and be equivalent to “and.” In these cases nor more often than not follows not or n't and can be seen as adhering to negative concord.

Lightning nor thunder nor a good sousing nor anything else didn't keep him from going.

I didn't take any toll off any orphans nor widows.

I didn't ask him when to go nor where to go nor nothing.

She won't bother me, nor she won't bother anybody else.

11.5 Negative Inversion. A negated verb form such as don’t, didn't, ain’t, hain’t, or can't may invert with the subject of a clause. (See also §18.3).

There's an old house up here, but don't nobody live in it.

Didn't nobody up in there in Greenbrier know nothin' about it till they run up on it.

Ain't nary one of 'em married.

Hain't nobody never set [the trap] for any bears since.

The house is so far up in the hills that when me and my old woman fuss, can't nobody hear us.

11.6 Contraction with not. In Smokies English a form of be or have or modal verb will or would may contract with its subject (more often with a pronoun than a noun), preserving the full form of not. Thus, that's not varies with that isn't, etc.

That's not a cow brute's skull. That's a human skull.

There's not near so many as [there] were at the time we came here.

Now my memory's not as good as it used to be.

No, they said, that's not a bear. It's a wildcat.

I've not tasted of it yet.

You've not met him, I don't guess.

I'd not yet learned how wary those fish were.

We've not had a warm enough winter this year.

I'll not say that I'm going to buck it.

I'd not care to drive a car.

12 Direct and Indirect Objects

12.1 Where general American speech prefers the reflexive pronoun forms when an indirect object is co-referential with the subject of its clause, Smokies speech often uses simple personal pronoun forms. In these cases the pronouns tend to be redundant.

I got me a little arithmetic and learned the multiplication table.

I got me a stick and was about to kill them [=black snakes], get shed of them.

I had got big enough to trade me in two or three pistols.

You can catch you a mole.

He put him a turnip hull on the end of his rifle gun so that he could see the darkness of the bear.

He wouldn't eat but two messes out of a big’un and then kill him another'n.

Well, they'd get them a preacher and let him preach a while. Then they'd change and get them another.

12.2 The pleonastic “accusative of inner object” occurs with a wider variety of verb than in general usage.

A man that ground-hogs it is a man that cain't help hisself.

I guess you fellers are behavin' it all right, aren't you?

They tried to run it over him.

John Lewis Moore's boy can pick it on the guitar.

13 Adverbs and Adverbials

13.1 The suffix -s may be added to some adverbs of place and time in Smoky Mountain English.

I don't imagine it was any worse than anywheres else in the mountains.

We learned we had to call him a long time beforehands.

They keep all over that mountain everywheres up there.

I get close around four hundred dollars a month, and it don't go nowheres.

They'd pull [the trains] in and take track up and put it somewheres else.

13.2 Adverbs (principally ones of manner or degree) without the suffix -ly are common in Smokies speech.

a awful ill teacher (= a very bad-tempered teacher)

I think it was a lady, if I'm not bad fooled.

There's not near so many as were at the time we came here.

We would hike the mountains 10 or 15 miles a day, searching careful as we went.

I have been powerful bothered for several days.

They don't like it real genuine. (i.e. very much)

Some of that country is terrible rough.

My family done tolerable well.

By the same token, good is a variant of well in adverbial contexts:

He knows [the song] good.

She could pull a crosscut [saw] as good as a boy.

Best, the superlative form of the adverb good, may take the definite article.

I've enjoyed it the best so far. (=very much)

I always thought they got along the best.

13.3 Intensifying Adverbs. Smokies speech has many adverbs to express “very” or “extremely.” In his investigations Hall found that the force of very had apparently weakened, i.e. “I'm very well” was reported to mean “I am fairly well,” and this semantic process may account in part for the numerous alternatives that occur.

Me and my brother went a-coon-huntin', but we never done any much good.

We had a awful rough, bad winter years ago.

That water isn't bad cold.

Newport's a mighty fine place for a young man to go.

Is that road much steep?; They said he never was much stout after that.

I used to trap for 'em, [but] never got so powerful many.

He was right young. He was just a boy.

It's a terrible bad place.

Smokies speech also has many ways to express “all the way” or “completely.”

The bullet went clean through his leg.

My cattle run clear to Silers Bald.

Uncle John Mingus was done dead.

They was plumb sour, and they would keep plumb on till spring.

They owned all this, plumb up to the gap.

I'll be covered slam up.

We worked till slap dark.

He was smack drunk.

13.4 Locative Adverbs. Smokies English has many constructions not found in general usage to indicate position, distance, or direction. These are most often employed as adverbs, but some may also function as adjectives to modify nouns.

thataway “that way”: When you're coming down thataway, they ain't many places to stop.

thisaway “this way”: I'll go around down thisaway below him, and you go down in on him; I was a-laying on the bank watching them bees just out thisaway from where the mud hole was.

yon/yan “over there”: I says, “Yon's the White Caps now”; She's in the field, up yan, gittin' roughness.

yonder/yander “over there”: They was some trees that stood all up here and yonder about in the orchard; I sneaked up in here with a horse from down yander where I showed you mine.

13.5 Other adverbs differing from general American English include the following.

afore “before”: I done what you told me afore, and it holp me some.

along (followed by a prepositional phrase) “approximately, somewhere, sometime”: Along in nineteen and thirty-three I went into a southern [CCC] camp; He had two brothers that was hid along down on the road that they had to go.

along “continuously, steadily, regularly”: We'd kill game along all the time; [He] probably might have sold a few apples along.

anymore “nowadays, at present” (in positive sentences): Anymore, of course, they use more or less sugar in the mash; Things changes so much anymore.

anymore (in negative clauses) “again, from then on”: He never remarried anymore.

anyways “to any degree or extent, at all”: Well, if you was anyways near to a bear, he would charge you.

anyways “in any case, at any rate”: Sometimes you would get more and sometimes less, but anyways from ten to fifteen dollars.

edgeways “edgewise”: Let's leave time for people to get a word in edgeways. (similarly, lengthways “lengthwise”)

everly “always”: He was everly going down to the store.

noways “in any way, at all”: We didn't have no use for it noways.

right “immediately, exactly”: You find that right today.

sometime “sometimes, from time to time”: Sometime it takes about a couple of minutes for 'em to come up.

someway “somehow, in some manner”: Someway Martha rolled a big rock loose, and it hit our big hog.

used to “formerly” (placed before the subject of a clause having a past-tense verb): Used to we didn't have as many cars around as we do nowadays; Used to, you know, there wasn't very much working on Sundays.

13.6 Miscellaneous Adverbial Features

In the Smokies ago often occurs with a present-perfect verb rather than one in the simple past (see §6.2). Yet retains its usage from older English in affirmative clauses (rather than, as in modern English, in only negative, conditional, or interrogative contexts). It is roughly equivalent to, but sometimes co-occurs with, still, in which case still always precedes yet.

The rocks is still there yet.

I have got the old collar up there yet that I used on him.

Some people still might use the signs yet.

I believe that old good book will do to live by yet.

13.7 Adverb Placement. The qualifying adverbs about, much, mostly, and nearly sometimes come after the construction they modify.

We had all kinds of apples anywhere you went about. (i.e. almost anywhere)

Well, they were all kinfolks just about, you see. (i.e., nearly all)

You been sleepin’ all day near about, and you done broke a sweat, and that's good for you.

The weather never got any colder up there much than it did here.

They didn't have anything much to doctor with. (i.e. much of anything)

They'd set fires every fall mostly.

They'd all moved out nearly when I got big enough to recollect anything.

I'm always at home nearly.

14 Prepositions and Particles

The dialectal character of Smokies speech is conspicuous in the use of prepositions.

14.1 Prepositions with Verbs of Sensation and Mental Activity. Hall found that traditional speakers sometimes used of after verbs of sensation (smell, feel, and taste) and mental activity (fear, recollect, remember), but the preposition added little if any semantic nuance.

Feel of it now.

Smell of it.

He said he tasted of everything he had ever killed, every varment, even a buzzard.

I ain't a-fearin’ of this man, nor no man that walks on two laigs.

I can recollect of him a-going to school.

I can remember of seeing the soldiers at the close of the Civil War.

14.2 Prepositions Differing from General Usage

a- (historically a reduction of the preposition on, this is attached to a variety of forms in Smokies English as an empty, redundant prefix):

1 present-participle forms of verbs (§9): a-going, etc.

2 past-tense and past-participle forms of verbs (§9).

3 prepositions: aback, anear, anext, anigh, apast, atoward(s), etc.

I'll shoot if he comes a-nigh me.

Just apast the river there they made a bend in the mountain ...

And the bear, it made a pass a-toward him.

4 nouns, especially to form adverbs or adverbial phrases of time, place, or manner:

I went back down a-Sunday.

It was away in the night when I got in to camp.

I didn't do it a-purpose.

5 adverbs of position, direction, or manner:

I've often thought how many preachers, as you say, would ride a-horseback as far as Gregory did from Cades Cove.

They went ahead there and went to running a-backwards and forwards.

He was a-just tearing that window open.

6 adjectives:

Most of my people lived to be up in years, but I had some to die off a-young, too.

abouten “about”: I never knowed a thing abouten it.

afore “before”: I allowed he'd return afore this.

afteren “after”: He never give me his check before, just what was left over after'en he had been out with the boys.

against/again “by the time of, before”: He'll be in town against nine o'clock; He didn't make it back again the night.

anent “close to, beside”: I fell back into the river and just took up right up in the water and was wet all over and got up anent them.

being of “because of”: Bein' of that, Mr. Hood, I just can't take anything from you for the death of Bill.

beside of “beside”: She came over and set beside of me. (of here represents a reduction of the original phrase by the side of)

enduring “during, through”: Did he stay enduring the night?

excepting “except”: Faultin' others don't git you nowhere, exceptin' in trouble.

for “because of, on account of”: I couldn't see across that log for the fog.

fornent “opposite, beside”: He lived over fornent the store; The bear went up a tree ferninst us.

in “within”: They was in three hundred yards of the top of Smoky.

offen “off, off of”: [We] took that hide offen it and cut it into four quarter.

on (after a verb to express an unfortunate, unforeseen, or uncontrollable occurrence): When my cow up and died on me, hit wuz a main blow.

on “of, about”: He was never heard on no more.

outen “out of”: He frailed the hell outen him.

owing to “according to, depending on”: It's owing to who you're talking to, of course.

till “to” (in expressions of time): ... quarter till five.

to “at”: Clay said he's afraid I'd be rotten spoiled did he get me everything all to once; I belong to home with your Ma.

to “for”: That bear was small to his age.

to “in”: Ever' bone [of a man's body allegedly murdered] was to its place but one.

to “of”: He was a brother to my grandpa Whaley; They were men to the community.

withouten “without”: I seed him throw a steer once and tie him up withouten any help.

14.3 Prepositions and Particles in Dialectal Phrases and Idioms. Smokies English uses prepositions in numerous ways that differ from general English.

14.3.1 With verbs (to form phrasal verbs).

cut down/off/on/up “turn down/off/on/up”

give out “announce”: They give it out that there would be some preachin'.

lay off “plan for a considerable time”: I laid off and laid off to visit Aunt Phoebe, but never got around to it.

leave out “depart”: Moonshining is just about left out.

listen at “listen to”: Listen at that pack of hounds!

read after “read, read about”; Of a writer [they say] , “He's the best I read after”; I read after it last week.

study about/on/out/over/up: I hadn't studied anything much about it; I studied on it.

study after “study under, follow after”: He never went to college. He just studied after Dr. Massey.

throw off on “belittle, disparage”: She was throwing off on me.

top out “come to the top of (a ridge or mountain); I went on and topped out at the Bear Pen

awful to, bad to (see §10.2)

stout to “stout for, strong for”: Aunt Sis is stout to her age.

thick of “thick with”: It was thick of houses, thick of people up there.

book of “book about”: I have a book of him.

brother to “brother of”: Ephraim was a brother to John Mingus.

14.4 Particles Extending or Intensifying Verbal Action

In some cases a verbal particle serves less as an intrinsic element of a phrasal verb than it does to intensify or extend the basic action of the verb. For example, in “he topped out” out strengthens the idea in the verb and gives it a perfective aspect (i.e., the notion of an action being completed), but it also specifies the meaning to “reach the top of a mountain or ridge.” The forms which appear most frequently in such contexts are up (as in general American speech), in, on, out, and down.

in: We dressed the bear and carried him in home. (Here in has both a durative and perfective force7).

on: Well, I'll come on; I started on up through the jungles.

up: The storm scared us up; He was all liquored up; They've got it (a town) renewed up.

out: Study it out [i.e. think it over] while you are bringing in the water; They left out of here. (= They departed).

down: I shot the bear in the mouth and killed him down; Quieten down a little!

14.5 Combination of Forms. A remarkable characteristic of Smokies speech is the use of two or more locative forms in a single phrase that both introduces a preposition and modifies the action of the preceding verb and thus may be viewed as either a compound preposition or as an adverbial phrase. Most convey physical movement. Rather than being pleonastic, they suggest a speaker's attention to the terrain and the adaptation of the language to the speakers and their environment. A hunter who says, “I started on up through the jungles” means every word he speaks. In saying “started on” he means that he resumed his course after having stopped. He adds up to indicate the direction of his progress and through because he was proceeding through thickets and woods.

I went right down in on him and give him another shot.

The bear run down under the mountain.

They was several houses on up around up on Mill Creek and up in there and on up next to Fork of the River back up in there.

The dogs was a-fighting the bear right in under the top of Smoky, pretty close up to the top.

An uncle of mine and a cousin [were] making liquor in above my home.

Later on, in a few weeks or months after that, they found a dead pant’er in across at the river bluffs down to the end of the Smoky Mountain in there.

Bradburn had a stack [of wheat] just in behind the schoolhouse out here at Shoal Creek.

We started wooding there, along not far from Polls Gap and a-going back in on toward Heintoga, behind the timber cutting.

It was just down where that road comes around, on down in below where that road comes around.

[I] carried two dogs part of the way out back down to where I could get to the truck to them.

He turned them loose [and] down through the sugar orchard they went out up across over on Enloe, back around to the big branch, out across the head of hit over on Three Fork.

There come one [bear] right up in above where he lived over there on Catalooch'.

The old tom cat went up in under the chair.

14.6 Prepositions are occasionally omitted in Smoky Mountain English, often following another preposition.

Back (in) old times.

He could count (in) Dutch and read Dutch.

She lived several years after his death, and she's buried out (at) Waynesville.

She lives over (at) what they call Corn Pone, Cascades.

14.7 Prepositional Phrases for Habitual Activity. A temporal prepositional phrase with of (especially with a singular indefinite noun as the object) indicate regular, frequent, or habitual activity, in one of three patterns.

of a + singular noun:

We would gather our apples in of a day and peel our apples of a night and put them out on a scaffold.

He farmed of a summertime, growed a crop of vegetables, corn, potatoes.

We would have singing of a night and of a Sunday.

He would go up there of a mornin' ... and then come back that evenin'.

We could put anything in that you wanted to of a winter.

of the + singular noun:

Sometimes I take a nap and then come back of the evening.

They don't have no one to rely on of the night.

of + plural noun:

My grandfather was troubled of nights in his sleep with what was called nightmares.

15 Conjunctions

15.1 Uses of Subordinate Conjunctions.

Many subordinating conjunctions in the Smokies either do not occur in general American speech or occur with different functions there.

afore “before”: That happened afore I left the Smoky. (i.e., the Smoky Mountains)

against “by the time that, before”: We'd oughta do plenty of fishin' against the season closes; I was repairin' the tire agin you came.

as “than”: I'd rather work as go to school.

as “that”: I don't know as they ever took him to a doctor.

as how “that, whether”: He reckoned as how he would stop by; I don't know as how I can finish it today.

being, being as, being that “because, seeing that”: We'll try another'n, being that'un paid off; Being as you weren't at the meeting, you don't get to vote; Being that the president was sick, the vice-president adjourned the meeting.

everhow “however”: He leased ever how many cars he needed.

evern “whenever, if ever”: Evern you do that, you'll come home and find a cold supper.

everwhen “when”: Everwhen we got there, Jack reached for his gun.

everwhere “wherever”: They had to get their breakfasts, eat, and be in the field or everwhere they were working.

how come (see §17.2).

how soon “that ... soon”: I hope how soon he comes.

iffen “if”: Come into the fire iffen you-ones wants to.

lessen “unless”: But some of them were awful sully—wouldn't ever talk lessen there was need.

like that “like, that”: It seems like that your best land is the most suitable land to build houses on.

nor “than”; He's a better fiddler nor me.

that (redundant after other forms, as in because that, how that, etc.; see §15.4)

till “so that, with the result that, to the point that”: The bean beetle got so bad till we stopped growing [beans] here; He liked it so strong till you could slice it.

to where “to the extent that, to the point that”: The coons was hung up to where they froze up and was alright; I got them to where they would mind what I'd say to them.

until “so that, with the result that”: I've done this until they could take and interpret the pictures.

whenever “of a single event: when, at the moment that”: What did they do with you whenever you killed that man two or three year ago?

whenever “as soon as, at the earliest point that”: Whenever you get to Big Catalooch, it's just across the mountain to Caldwell Fork.

whenever “of a process or extended period: throughout or during the time that”: My mother, whenever she was living, she just told you one time.

whenevern “of a periodic or intermittent event: when”: Whenevern it was snowin', you couldn't get half the logs out of that brush.

whenevern “of a one-time event: as soon as”: Whenevern we got married, we went on back to Marks Cove.

without “unless”: You couldn't cow him [=a dog] without you whipped him.

withouten “unless”: I won't go withouten you do.

15.2 SME features two types of tense-less clause, both introduced by subordinate conjunctions. One involves the usage of a verbless absolute introduced by and, interpretable as having an elliptical form of be, being subordinate to a preceding finite clause, and having the sense “what with” or “at a time that.” The OED3 attests this usage, which ultimately has a basis in Irish or Scottish Gaelic, from 1500 and characterizes it as now regional (chiefly Irish English).

They all wore Mother Hubbard dresses, and them loose.

That woman is doing too much work, and her in a family way.

He would steal the hat off your head, and you a-lookin' at him.

Dan Abbott ... just spoke in there a while ago, and all the congregation standing there.

We had nothing to do, only just pick it [=the gun] up and start for home, and Jack naked, all but his britches on.